I’m standing in an enormous white-tiled consumerist’s heaven supermarket. Everything I need is available at a price, even half the price. I drove down here in a frenzy. All the sinuses on earth are exploding in my head right now. I know the cure.

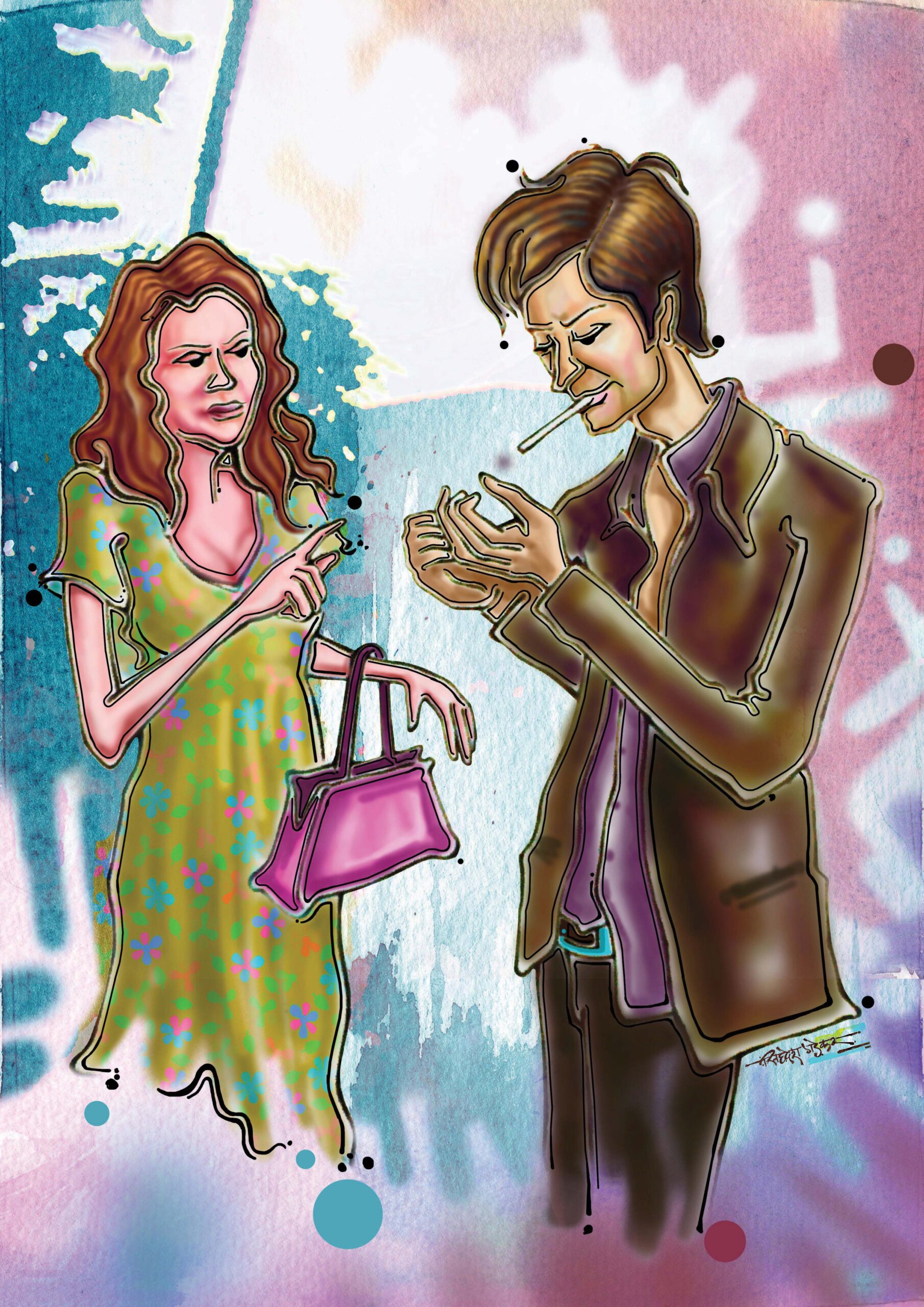

It was Natasha who stopped me from smoking, the anti-smoking lobbyist that she is. Puffing was the one way I could unwind, let go—no need of the conventional spa treatment. A packet of Wills and the fire in my gymnastic mind died down. Driving like an F1 racer, at the risk of parking tickets and broken bones, didn’t help.

Natasha is beautiful, forgive me for reminding myself. She has this unearthly beauty about her that made me light my cigarette one day and think about her moon face and the moon halo that poured out.

I stubbed my cigarette as she just didn’t approve.

I met Natasha in a supermarket like this one. She was in the other queue. The other customers were distracted, on their phones, texting, yawning, scratching. But she looked ahead and that’s when I scanned her proportions… “ Shameless dude, you checked me out proper,” she would say on those days when she was in a better mood, on days when she was not troubled by her genetic predisposition toward hypertension, and especially on those days when she did not have her PMS.

Ever since I moved in with Natasha, I’ve been going through this biologically warped cycle myself. I mean why couldn’t she be like Mom? She never let me know she had the chums. She would hide her debris in the obituary section of the newspaper and curl it up into a minuscule innocent looking ball. Then she would tiptoe silently into the kitchen where we had our waste disposal and when that was over, she would heave a sigh of relief.

I found out about this ritual when I was eleven. I never let Rahul see it. Mom was bragging to an auntie, who looked at her with admiration. “How long can you hide these things from him?” auntie’s admiration turned into cynicism as she saw the shadow of her 16-year-old daughter pass. “As long as I have to,” Mom said withdetermination.

My Mom, poor Mom; she was saving me from the future. If Natasha with her moon face and aquiline nose had mom’s compassion, we might have been, why not, married.

Natasha is modern that way. “We cannot commit unless we understand each other totally,” she would tell me when I asked her why we couldn’t just settle down and get it over with. Mom didn’t buy this arrangement. “It’s not healthy,” she told me when I came home on long weekends and Natasha was out of town doing ‘her girl things and me-time’ and things that should not enter the ‘male gaze’.

Dad just snorted as he surfed through two hundred cable channels, the TV screen reflecting back at me

through his record-breaking 25-year-old glasses.

Natasha approved of Dad in many ways: “He’s perfect in an old-fashioned way, which I think is good.” Natasha’s parents were in the Army; so she’s a stickler for time. No need of a clock when she’s around. Or a calendar; as her biological clock, like her, is bang, punctual.

As are her moods.

When she has the pre-menstrual syndrome (I googled on it just to cross-check her claims), Natasha has the right to look unkempt and absolutely unholy. She drags herself to office with a concoction of ayurvedic drugs in her handbag, which I suspect make her moods worse.

She included me in this exclusively female experience by texting ‘You never know when it is creeping into you, waiting to take away your happiness.’ I did not respond to that as usual as, I was in a meeting with Gagan.

This meeting was about appearances versus reality. Gagan wasn’t on the interview panel when I landed the job and when he did get to meet me, he found out that my contributions to company standards were unenviable. He called me into his cabin for brainstorming sessions and created an image of greatness by posing in front of a long mirror he placed before his table. Mirrors increase the space factor, he said. I thought it was narcissism.

Besides Natasha, I did have a life, if slavery was a life definition. Natasha talked about my work as nothing but talking. “All you do there is talk. In your grey suits some days and in casuals on Saturdays. Talk on the phone, the internet, face- to-face till midnight…what’s the point of the social institution of couplehood?”

She had a point. Talking, until I came home with nothing to talk about at all to this beautiful moon face with the swan neck who wasn’t waiting for me as the waiting was over. No offence against women, but Natasha in particular is theatrical. She reads Plath (for god’s sake) and she fights for women’s rights by making meaningful comments on women-only websites.

Post midnight, I wanted to avoid even an attempt to converse. Natasha was plopped in an armchair, sipping at some herbal concoction, and I thought to myself, ‘damn, it’s that time of the month (her text came to me like an afterword)’. There were little bubbles coming out of her head like I have to make her happy, but I won’t.

She arched her eyebrows and said, “You were good at wooing me, sweeping me off my feet, and now look at you, a mule.”

“Mule? Excuse me. You’re the one with the nine-to-five job. I have commitments.”

“And what am I?” she said as she twirled her artificially (or naturally?) frizzy hair between her fingers.

“Am I some kind of fruit cake waiting for the devouring man to come along? I’ve been trying to reach you on the phone. I called Gagan and he said you were in a critical career patch.”

“Patch? I told you not to waste your life talking to Gagan. What are you, some kind of spy? If I don’t pick up my phone, I’m in a meeting.

The last person you should call is him.” All my Gagan hostility came flying out. I wanted to end the conversation, “What’s the time now?…12…it’s way way past your clock.”

Natasha’s moon face was beginning to evaporate. All I could hear was the needle twang of her voice saying, “I’m not well. You don’t even care about my issues.”

“Your issues, your issues….what about my issues? I’m through with ego-dripping upstarts. I come

home for some peace and here you are with your pathetic pre-period pains!”

And then a fight ensued, the likes of which I had never encountered. Whenever I fought with Mom I would have the last word, Mom would then sob and I would apologise. I’ve never been able to fight with Dad who’s been surfing TV most of my living memory.

Natasha and I didn’t speak for a week after the big fight. We lived under the same roof like zombies. I made my breakfast. I watched a lot of TV. I started going inward like a yogi. Gagan complained about my ‘indifference lately and how it could affect my career graph.’

Until I got jolted by a phone call.

It was one of Natasha’s friends. Natasha had been crying in a restaurant. Something about ‘irreconcilable differences’. As she wiped her elegant nose and perched her RayBan over her lush hennaed hair, she tripped and fell from the stairs. Then I heard words like ‘serious’ and ‘hospitalised’. Like a scene out of a movie, I rushed to the hospital.

Good thoughts were pouring into my head. Why had I made moon face with the slender fingers unhappy? She who smelt of talcum and Chanel Dior. She who smiled at my lame accounting jokes. She who played darts with me as I decimated Gagan’s photograph. I remembered with my song-filled neurons our first date at Coffee Day and how the chocolate cake oozed from her lips. Then that subsequent meeting at Forum Mall when she let me hold her slender fingers decorated with snake-shaped rings and green and blue nail polish. How she appreciated my gifts and poetry…how she blushed and made the right innuendoes. And now…

She had a fracture. Nothing serious. She just needed a lot of rest. So I wheeled her home and made us dinner. And did some small talk, explaining the perils of leaning by a staircase with pin-pointy heels that make a girl’s legs sexy but not necessarily smart. The eerie silence that our fight had made was replaced by the sound of my concern. I kept wondering whether that was a hollow sound. Was I caring enough? Was I doing the right thing? And then she almost jumped off her chair. “It’s started!” she screamed and looked at me like a lamb approached by wolves.

I knew what the sound of her voice was about. It was the shrill cry of a woman with chums. “I need a pad.”

“A what?” I pretended to think in terms of notepad.

“A sanitary napkin,” she wailed.

So I delved into the almirah, through heaps of sequinned salwars and saris, through drawers choking with paper and cupboards brimming with books. In search of one, any, solace to quieten moon faced Natasha with the pouting lips. “I think I’m out of stock,” Natasha whimpered. Natasha, out of stock? She stocks three bags of rice three months ahead. She’s the proverbial house sparrow minus conservatism. I thought maybe I had heard wrong. “No, seriously Rahul, I’m out of Stayfree. Could you just hop around the corner and get me some?”

Stayfree, Carefree, Always. Pictures of happy women dancing in white flashed before me… the names that frighten men. “No way,” I said calmly with an animal ferocity.

“What do you mean, no way?

I thought I had a fracture and it was all your fault I was so upset and tripped.”

“Look anything but that…”

“How can I go to the chemist and get it when I can’t even move?” Natasha was starting to whiten. “I’m losing blood. Please

Rahu, hurry…”

I couldn’t take the pressure. The day was collapsing on me like a tonne of bricks, my boss who was trying to throw me out, my incompatibility with Natasha and now her desire for the impossible.

“I’ve never bought it Nats and I never will. When was the last time you shopped for condoms? It’s always me.”

She cut me short and a Plathian rage filled the apartment. “How can you compare the two? How can you Rahul? This is my body we are talking about and I need a pad.” Natasha was shrieking, “You don’t hesitate to touch me, any part of me at all! And you are frightened of buying a 30-rupee packet!”

I left with the ugly sound of her voice echoing in my eardrums. I thought of the first time I had bought vegetables for Mom. I thought about the diamond ring I was supposed to slide down Natasha’s ring finger. I drove with ambition and speed. And now I stood amidst a sea of sanitary napkins. Without wings and with wings. With net or without. I couldn’t absorb the gravity of my emotional turbulence. Buying

a sanitary napkin equalled a compromise.

I circled the section several times.

I purchased a conglomeration of items I did not need— a hairbrush, a pair of bathroom slippers, a toilet cleaner, ginger beer, and other things. And finally, finally, I left the supermarket. It was dark and the moon was smiling at me with a star for a bindi. It was really dark, the street lights stood unemployed like sentries in the dark. The silence seeped into me and I was surprised that I had ditched the love of my life for a stubbornness that was a part of my genetic disposition.

Something Mom had ingrained, perhaps, in little ways—by telling me not to cry like a girl, or stopping me from playing house, or giving me a special sweet as I was her only Son. Or Dad had, who can tell? By his quietness towards Mom and the invisible relationship they had confined to rituals like kumkum and mangalsutra. Or maybe it was my way of giving in to this terrible craving

I had for over the entire last eight months, since Natasha banged her frizzy hair against the musty walls and demanded I surrender my bad habits for her.

lll

I pick up a cigarette from the Wills packet (that I had picked up by the way) and light it ceremoniously. I have a cat for company as I lean against my Getz and inhale a large circle of smoke. Natasha with the pensive face seems to be saying “It’s bad Rahu. Your lungs will resemble Bangalore soon — a polluted treeless space.” She is right of course, but I feel my sinuses clearing up already.

The cure feels good.

- Neelima P.